20th Century Brutalist Icons

Archer Humphryes breathed new life into a trio of Brutalist buildings with projects for The Standard London, Queen Elizabeth Hall on the Southbank and, Philips Haus in Vienna. Julie Humphryes celebrates the sustainability and regenerative properties of these fantastic concrete icons.

Brutalism is the ultimate Marmite genre of architecture. With its bold form and up-front showcasing of the raw beauty of concrete, it has always attracted vocal criticism. So many pioneering buildings have been neglected and deteriorated before being lost to redevelopment– from Owen Luder Partnership’s Trinity Square car park in Gateshead, to John Madin’s Birmingham Library and the Smithsons’ Robin Hood Gardens housing. Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s lauded but obsolete St Peter’s Seminary in Cardross has been left to ruin for years. Yet over the last decade or so, a revival in appreciation of Brutalism has brought fresh hope for some. Erno Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower has morphed from down-at-heel to desirable Brutalist chic. The Park Hill mega-estate in Sheffield is slowly, but surely, being revived by Urban Splash.

Our Brutalist reinvigoration projects demonstrate that this strong visual identity can be an asset, rather than a hindrance to reinvention. Unlike so many of this genre, all three buildings had enjoyed successful occupation. They have now proved their sustainability further, with The Standard and Philip Haus both accommodating a conversion to a new use, and the Queen Elizabeth Hall foyers retaining their original function and proving capable of sympathetic reinvention. As a result, we have been able to attract a new audience to each. These bring with them their own youthful magnetism, re-energising each space anew.

The Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) is one of a trio of Brutalist arts venues at the Southbank Centre along with the Hayward Gallery, and Purcell Room. The complex was designed by the London County Council’s Special Works Group of architects between 1963-68, and the QEH first opened in 1967 with a concert by Benjamin Britten. Using austere decoration as the backdrop and limited fenestration, the complex’s varying masses of concrete are arranged to avoid competing with the nearby Royal Festival Hall. It is considered a triumph of the plasticity of concrete form that is best associated with Brutalism today.

QEH has maintained its original usage as a music venue for the nation as part of the wider arts complex, and has remained a leading light for avant-garde and classical musical performances. Archer Humphryes revitalised the venue’s interior public space, including the ground floor café and bar, as part of a major refurbishment between 2015-18, creating a ‘living room’ for the London community, led by The Southbank Centre as client.

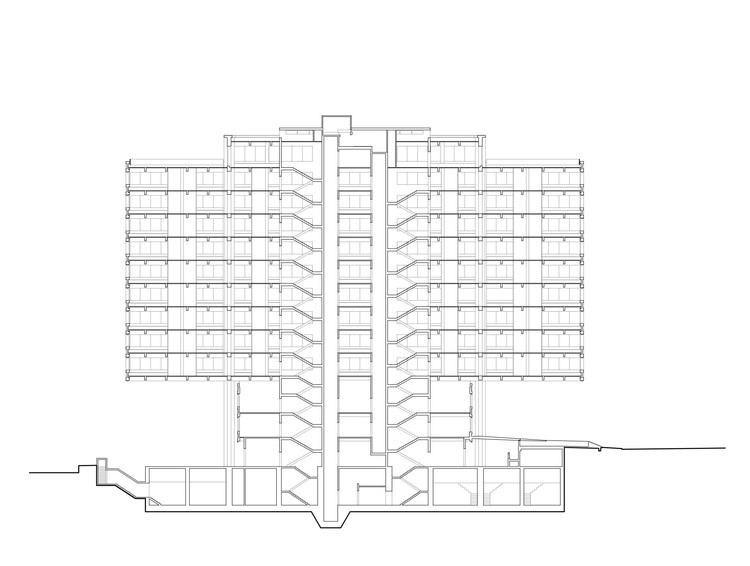

Our other two Brutalist projects were adaptive re-uses for buildings designed originally as offices. Once the headquarters of Philips, Philips Haus was designed in 1962-64 by Karl Schwanzer and is emblematic of the visionary ideals of the time. With its dramatic cantilevering wings and imposing presence, it remains a landmark in Vienna today, and still conveys the visionary ideals of its pioneering architect. Our project was to re-invent the aesthetically uncompromising structure as apartment living, drawing on our hotel design experience and making the most of the column-free plan and continuous horizontal glazing around the tower. We created 16 apartments on each of the 11 residential floors, and a new neighbourhood restaurant and bar on the ground floor. The top floor is reinvented as a chic new destination including an observation area and swimming pool.

Our most recent Brutalist project is the conversion of a 1970s former office building for Camden Council into The Standard London, a chic new hotel for the Standard hotel group, which was also our client for Chiltern Firehouse. This 266-bed project demonstrates the potential for sustainable transformation that so many robust Brutalist buildings share. Rather than demolition, Archer Humphryes proposed – and delivered - an amplification of the curved white windows and façade, with a new glass rooftop addition. A red, external pill-shaped elevator leads directly from the street to the roof bar, which has proved popular with London’s bright young things.

Modernist concrete buildings aren’t new to hospitality. Provenance can be found in the Hilton Istanbul Bosporus designed by SOM in the 1950’s. Easily recognised in Jules Dassin's 1964 film "Topkapi", as the backdrop to the story’s characters, it was constructed in competition to a hotel that was being planned by the Soviets. The project marked rivalry in the height of the Cold War and became a strategy for hotel design ‘export’ across the region for the USA - being interpreted as a symbol of power and strength.

In contrast Geoffrey’s Bawa’s Hyatt in Bali with Palmer and Turner was conceived as a continuation of local vernacular gardens with water and landscaped terraces embedded in the architecture, influencing decades of hotel design and the typology we now refer to as ‘Tropical Modernism.’ Concrete expression has continued to be relevant in the sub-tropical resort, with Bawa’s complete works being published in 2002, once more influencing a new generation of architects and designers. Notably the late Kerry Hill whom as a young architect worked in Hong Kong for Palmer & Turner in the 70’s was placed on the Bawa Hyatt project– which I echoed as a student in the 90’s working also for Palmer & Turner, revitalising hotels across the sub - continent.

All our three projects share a common approach that celebrates, rather than diminishes, the buildings’ Brutalist spirit. We strived to express the concrete form and its tactile nature in both the exterior and interior. We created vibrancy and vitality through the use of strong colours and stark whites to contrast with the austerity of the grey concrete, and brought light into the deep plans of the public areas and circulation areas where natural light wasn’t abundant. We added warmth through timber and reflective surfaces, softening the acoustics through upholstered surfaces and most importantly connecting to external green areas.

We hope that our projects help demonstrate the adaptability of great Brutalist buildings, and in particular, their potential for hospitality use – interestingly, it’s just been announced that Marcel Breuer’s 1970 Brutalist Armstrong Rubber Building in New Haven, Connecticut, is also to be converted into a hotel, opening this year. Through careful re-imagining, these buildings have the flexibility – and aesthetic kudos – to attract new audiences and sustain new uses. Rather than perceiving them as candidates for demolition, they should instead be embraced for their distinctive design, and explored for their considerable re-use credentials.